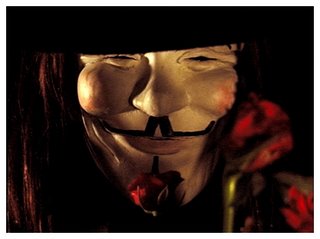

V for Vendetta

This post is in response to a viewing and discussion of the film "V for Vendetta" that has been organized by Chris Limburg in Madison, WI for tomorrow. Chris' invite blurb is:

"As a pacifist, I loathe violence.

This movie ushered me to a seat where I paused to reconsider that commitment.

I took that pause seriously and think it is worth talking about in a forum."

Having recently seen the film, I wish I could be a part of the event. In lieu of my absence I decided to write a review commentary here.

The film is about social change. Social change is so normal that almost 100% of the time we don't notice it. It is in fact so elusive to our reptilian sensory observatory powers that if we make no cognitive effort to observe social change, it is not until catastrophe or some equivalent critical mass that we pick up on it. The glacier-paced speed of change makes things seem the same day in and day out, but with conscious reflection one can begin to guess which events may impact the future course of society. I feel founded in saying that social change is constant and normalized in part because of the experiences I've had in my recent move to Los Angeles, CA. Talking with friends on the phone from Madison makes me realize that even after only a few weeks the Madison I knew and will always remember is already gone. The changes are subtle but distinct. Different ways of thinking, interacting, and flowing are creeping in and replacing what I knew. The degree of subtlety of the change is such that I could return to Madison and figure things out pretty quickly, but the most interesting thing is that without my absence I'm guessing I would not have noticed the change.

So, V. V is a prophet. V wants power. V takes power violently. He justifies the wielding of violence to take power so that he can make the world in a way that he thinks is right, and he can't do it without the support of all those people, hence the propheting. Sounds like a wacky religious thing to me. So the question is why does it feel so good to watch V kill the bad guys, show the light to all those people, and blow up the city? It feels good because it supposedly restores our idea of human rights to the masses who have been stripped bare practically without their knowing. The social change that put the masses in a police state of uber surveillance and punishment happened outside the sensorial realm of most observation. Combined with some governmental lying and trickery even the quick ones in the bunch were duped or forced into this, what we would recognize as an inhumane state of affairs. It feels good to watch because there are so many analogs to the current federal administration and political environment in the United States. It speaks to what many Americans really want to see happen to the government, i.e. a fantastic overnight upheaval. It feels good to watch because as viewers we are given a privilaged position that makes V look smart and outside of the uber violent surveillance police state, a place we'd all probably like to be. Platially he is outside of it -- he has his secure Bat Cave, and he can freely roam the streets. The price he pays for his free flowing, though, is where the moral dilemma rears its ugly head. He secures his freedom with violence and murder. Sounds like our least favorite president to me. Summary so far: Bad guys wield power through violence, we don't like. V wields power through violence, we like. What makes the film morally engaging is that it's hard to imagine V or anyone like him succeeding without the use of violence. We see him and think "well I guess there's no other way, we'll just have to use violence." The peace movement has long (and correctly in my opinion) recognized this as a dangerous response. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously quoted that "Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars... Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that."

Power has been shown over and over again as directly linked with violent persuasion. You can't have a revolution without power, and you can't have enough power for a revolution without violence. The crux of the dilemma, then, without discussing the meaning of rights and justice, is how to change the direction and velocity of society without power. My feeble response to a potentially unsolveable puzzle is that the only thing we can consciously change after ridding ourselves of power is ourselves and the way we interact with the environment that surrounds us, including people and non-people. Ridding ourselves of power means ridding ourselves of the desire for control. Now if only we could tell everyone to start doing that at once, it just might work. I know, we could take over ABC and shoot out the message on the airwaves. The age of peace is here. 1, 2, 3, now.

4 Comments:

Nice comments, Nick. I had practically a dissertation that I wrote on this subject, but it got pretty long winded so I decided not to post it. Suffice it to say that I will be watching this movie.

Hmm, actually I decided to start my own blog. http://the-gas-chamber.blogspot.com/ Sort of a morbid website name, but I'll try to make it fit.

By Gary, at 2:25 PM

Gary, at 2:25 PM

Interesting thoughts. Wish I could be there for Limburg's discussion party, too. I loved that movie - well, most of it, anyway. I also loved how Natalie Portman questioned V about his violent methods, although I wish this had been played up a bit more. My thought on the question at hand echoes the verse from Ecclesiasties (SP?) in the Bible (can't recall the precise verse,) later made popular in a Byrds song: To everything, there is a season. If a small amount of violent action is necessary to remove a far more violent and overly opressive government or other entity, and no other method will possibly succeed, then it has to be.

By The Dude, at 11:52 PM

The Dude, at 11:52 PM

I like the morbid name, Gary. I'll definitely check it out. As for the "kill one to save them all" approach: it still makes me nervous. A Utilitarian calculus (made famous in the West by John Stuart Mill, search "utilitarianism" in Wikipedia) has still always been founded on the view that harm to none will bring the most happiness to all. Instead of asking how the bad guys' power can be stopped, we should be asking why they are bad in the first place?

By Nick, at 7:49 AM

Nick, at 7:49 AM

Obviously, it is ideal to harm none, but often, those oppressed have no such luxury of making that evaluation, or else it's brazenly obvious but cannont be changed. Non-violent confrontation works in certain circumstances - it has to take place within a relatively open society. Gahndi and Martin Luther King were able to succeed because their actions brought attention from the general public, who were able to influence policy makers in their respective societies.

However, the peaceful marches in Tianamin Square in 1989 and in Burma in 1988, or the Prague Spring of 1968, for example, had decidedly different results, and the oppression and violence at the state level did not end. I'm guessing that if V had led a peaceful resistance to the chancellor's brutal and violent rule, it would have much more like Tianamin Square than Martin Luther King's March on Washington.

But that's just my take.

By The Dude, at 3:18 PM

The Dude, at 3:18 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home